Lawrence Berzon remembers visiting the American Museum of Natural History as a child and being inspired by the art in the dioramas. They were mostly animals, insects, crustaceans, cavemen, and they were very real. He studied these dioramas in a way that had profound and lasting impact on his work. It’s about the concept rather than featuring the sole image in the center of the picture.

Berzon has always been a storyteller. The evolution of his work is a progression from the graphic novel to multi-frame painting. Then sculpted frames were added to the paintings, and ultimately frames were created within the image. These frames inside the image eventually evolved to become dioramas. Then the dioramas began to move and became kinetic sculptures.

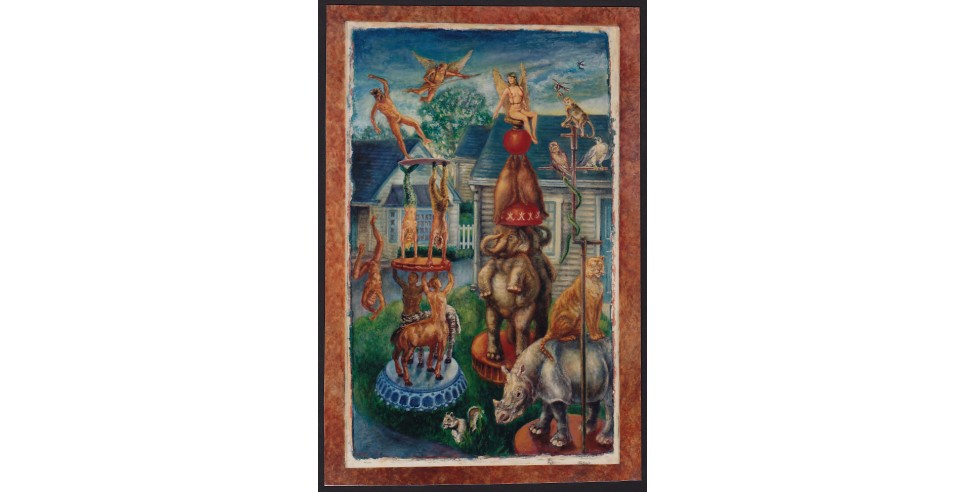

Today his work lives where art, literature and mythology converge. One painting, The Myth of Performance, captures mythological creatures, angels, demons, centaurs, and an occasional mermaid, in the stillness of their movement. Wild animals, from the jungle and the forest, clamor in a freeze frame, suspended mid-air as though time is altogether another dimension. This painting is one of his many works that allude to the myth of performance as social allegory.

His paintings from his “A Compulsion for Beauty” collection address our culture’s unhealthy obsession with feminine perfection. In Observers, a naked woman stands in the midst of a room full of fashionably attired women. All eyes fasten on her, judging her, as though she is being sold at an auction. The Alteration depicts a woman seated by a pool. She is stitching patterns of leaves and flowers on her shapely legs, but feels no pain from the sharp needle.

The partially undressed woman in Private Meeting sits at her vanity. Surrounded by a panoply of figurines, wall plaques, pictures, the drawer knobs on her vanity and the handset of her phone, everything is cast in her own image and likeness. She is her own sycophant, consumed by the annihilation of self-love. Private Meeting, described as a “Boudoir of Narcissism” in Art in America, leaves little to the imagination while furthering the discourse on social allegory.

In Aspirations, a woman is convalescing in a hospital bed. Her one limb is a magnificent wing, the other, an arm, is being wrapped in bandages by a doctor. The painting belies our worst suspicions about obsessive plastic surgery. Women indeed have become victims of their own self-concocted and self-ascribed social norms. The bar aspiring toward today’s standards of beauty has never been higher and so punishing.

According to Berzon, “In these scenarios, single or multiple characters interact with themselves or their surroundings, forming modern social allegories that both reflect on the human condition and conflate with the fantastical.”

Berzon has created many frames for his paintings. Elements of the frame are in the painting and elements of the painting are in the frame. He discovered that making frames for the individual paintings, and for the individual panels of diptychs and triptychs, “layer more twists and turns onto the story.”

When the sculpted elements of the frames moved inside the picture to create a diorama, the works became three-dimensional. It was only natural for the three-dimensional works to evolve toward movement. Dioramas are fitted with motors, computer chips, cams, imbued with original soundtracks, and emerge as fully interactive audio-animatronic sculptures. The multi-faceted layers of storytelling are hidden within the sculpture. Intricate images are completely concealed until the viewer inserts a coin or presses a remote control and is granted access to an intricate, animated performance.

Through the interaction with the viewer, the dioramas break the third wall. Whimsical, frightening, laugh-out-loud hysterical; his kinetic sculptures can be all of these things, but seeing is believing.

For example, the House of Myth “Intertwines Medusa, Sisyphus, and a house to explore expectations and transformation. Two Medusas struggle on a hill, one petrified by the other’s gaze. Just like Sisyphus, the remaining Medusa endlessly pushes the stone uphill, only to see it roll down again. The house embodies a mystical realm of boundless possibilities.”

The audio-animatronic sculpture The Censor delves into the many layers underlying a man’s infatuation and obsession with a woman. The man’s tattoos reveal a woman emerging from his skin. The man’s head opens, revealing smaller versions of himself as he erases past relationships. The man’s head opens, larger and wider, to reveal his identity being subsumed by his love for this woman.

Another audio-animatronic sculpture Purge Your Anxiety offers remedy for the collective anxiety of the post-modern culture. Incessant stress spawns demons that grow inside of us and take control of our inner selves. Stop the demons. Purge the anxiety. Focus on positive thoughts. Deposit 25 cents and the exorcism will begin.

Berzon said, “Different things occupy the space at the same time and different things are happening simultaneously.”

Lawrence Berzon began his studies at the Art Students League in New York City and also attended the Rhode Island School of Design, the San Francisco Art Institute and the New York Academy of Art. Early on, he studied with Caesar Borgia, a portrait painter. Borgia had a stellar background and had studied under the illustrator Frank Reilly, who also had taught at the Art Students League in NYC.

There are many artists whose technique Lawrence Berzon admires. He gives special note to Caravaggio, Titian, Francis Bacon, Balthus, and Picasso, all of whom are worthy of admiration but do not exert influence on his work. He does reflect on the work of Hieronymus Bosch. “Each one of those images means something. Back in the day there was a visual language that was part of the painting.” Bosch tells stories, but each one of the images is also a symbol and possesses a deeper layer of meaning.

Berzon likens Bosch’s work to a visual language, almost like hieroglyphics that are woven within the story of the painting. Around Bosch’s time in the 1450s, there was a fear of repercussion from political and societal forces. The breakdown of freedom of expression made it necessary to tell stories through symbols and original hieroglyphics.

Berzon has also been establishing his own visual lexicon. “Loss and transformation are fundamental aspects of life,” he said. “I explore these concepts through various symbolic representations capturing moments of vulnerability, betrayal, and renewal.”

Often he visits the work of writers rather than artists. In his estimation, social allegory famously has its place in literature, too. George Orwell’s Animal Farm did that, as did A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess. The glossary in the back of the book included a language to convey what the characters were really trying to say in the narrative. “One of the great things about speculative fiction is that it comes up with a whole language.”

Some of Berzon’s work is self-referential; he has developed a visual vocabulary that he revisits. “My skills have increased. I see the images (from the past) and I build on the rawness there.” He enjoins the thinking of Joseph Cornell, who creates boxes with words in them, or Joseph Campbell and Carl Jung, who mine the visual, the extension of dreams, and the meanings behind symbols.

Performance is not entirely a myth. Lawrence Berzon is a tireless practitioner of making sure his work demonstrates this concept. “I’m trying to tell stories that are socially relevant and provoke thought,” he said. “The use of symbols drives the work. Multiple layers of meaning can be found. My art is rendered to seduce the viewer to look at it.”

To learn more about Lawrence Berzon and his latest works, please see his website: lawrenceberzon.com.

Author’s Note:

The “Myth of Performance painting with frame is 40.5 x 21 inches and 2.5 inches deep. Berzon created and painted the wood frame. The picture is oil on linen and wood with auto-body putty.

Descriptions of Paintings Referenced:

https://www.lawrenceberzon.com/work/paintings/

Private Meeting

Oil on Linen, 2000, 50.5 x 40 inches

The Alteration

2007, oil on panel, 22 x 17 inches (elements of painting in the frame)

Observers

2007, oil on panel, 16 x 20.5 inches (elements of painting in the frame)

Aspirations

2007, oil on panel, 18 x 19.5 inches (elements of painting in the frame)

Links to Kinetic Sculptures:

House of Myth. 2023. Oil paint on cast fiberglass; epoxy resin; wood construction; audio-animatronics.

15.5 x 31 x 15 inches (closed)

19 x 31 x 15 inches (with interior sculpture revealed) https://www.lawrenceberzon.com/work/kinetic-sculpture/myth-of-the-house/

Censor. 2023. Oil paint on cast fiberglass; epoxy resin; wood construction; audio-animatronics

22 x 33 x 17.5 https://www.lawrenceberzon.com/work/kinetic-sculpture/censor/

Purge Your Anxiety

2019. Oil paint on fiberglass, wood construction, audio- animatronics. 48 x 15 x15 inches (closed) 89 x 15 x15 inches (with interior sculpture revealed) https://www.lawrenceberzon.com/work/kinetic-sculpture/purge-your-anxiety/

#

Patricia Vaccarino has written award-winning film scripts, press materials, content, essays, articles, book reviews, and eleven books, including the Yonkers Trilogy, and several nonfiction works, including The Death of a Library: An American Tragedy. She divides her time between homes in downtown Seattle and the north coast of Oregon. Her latest novel, Maya Darling, showcases a painter of rare talent who reclaims her memory and her art after a powerful art dealer destroys her life. Goya’s fifteen “black paintings” set the mood, and the visual rendering, to tell the story of Maya Darling.